A sustained supply of Steel scrap is central to reach Net Zero targets

There is rising future demand for scrap steel in the UK

Scrap consumption from the steel sector could nearly treble by 2050, increasing up to 7Mt per annum. This would be the result of greater uptake of Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) production alone, without assuming any increases in actual steel production. Even at the more conservative end of the range, we see scrap consumption rising to 4.2Mt in next three decades. In the short term, the announced new EAF capacity at Port Talbot alone, will likely consume up to 2Mt more scrap than the site’s consumption today. That’s a nearly 70% increase in UK scrap consumption from around 2027, when the new EAF is expected to be operational. Proposed plans from British Steel would increase consumption further as early as 2025.

Demand for scrap steel will also rise globally in the future

Rising global demand for steel coupled with steelmakers transitioning to lower carbon production methods will drive up demand for scrap in the coming decades. The global scrap market is currently estimated at around 600-650Mt and demand is expected to rise to 800Mt by 2030 and around a billion tonnes by 2050.

Restrictions on global scrap supply

The EU is planning to introduce changes to its Waste Shipment Regulation from 2027 that will restrict exports of scrap to non-OECD countries that cannot demonstrate they can treat waste sustainably. These new restrictions will then mean that many of these countries supplied by the EU will look to other origins to source scrap and this will add further pressure to the UK’s supplies, in both volume and price terms. In addition, 43 countries have restricted their export of ferrous scrap, whether through export quotas and taxes, licensing or outright ban. This amounts to 77% of crude steel globally being produced by countries that have introduced or are planning to introduce measures that will, in effect, limit their export of scrap.

Environmental impacts of scrap

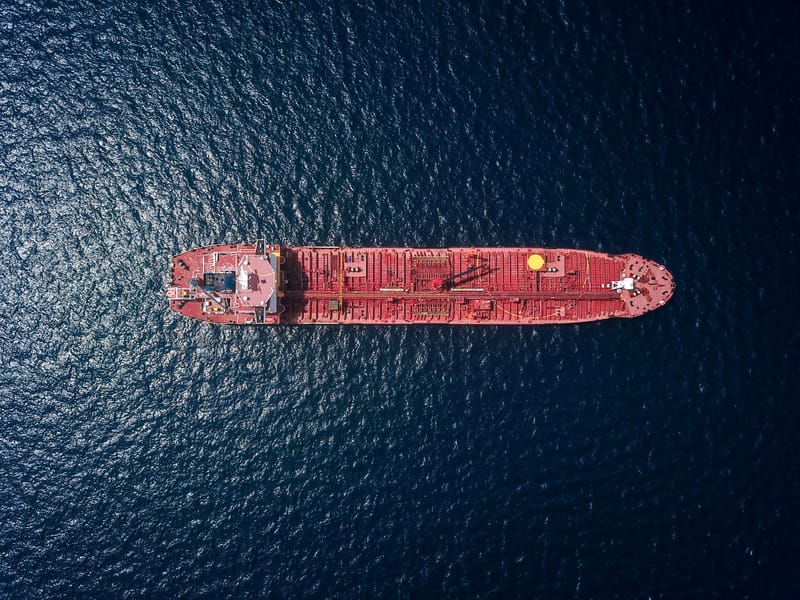

The UK currently exports 80% of the scrap it generates, resulting in higher carbon footprint than recycling in a higher carbon footprint than recycling in the UK. Based on the current carbon intensity of electricity production in different countries and transport related emissions, it is estimated that our export and subsequent re-import of steel gives rise to an additional 1.5Mt of CO2 each year. Approximately 50-60% of UK scrap exports currently go to non-OECD countries, many of which have much lower environmental, as well as health and safety standards.

Maximising value from the UK’s scrap supply

Ferrous scrap contains economically significant volumes of other valuable materials such as copper, nickel, aluminium and manganese. The current practice of exporting lower quality grades of scrap without advanced sorting, means we miss out on the opportunity to recover these other non-ferrous materials.